Keep Teaching: Choose Your Learning Mode

In the next sections, we offer brief discussions on each learning mode to help you interpret the official CSU learning modes, and make the best selection for your own courses and teaching goals. In choosing your learning mode, we encourage you to:

1. Consult with your department first, since departmental guidelines and requirements should hold top priority.

- Per policy, “department faculty, in consultation with college councils, are responsible for deciding” the learning mode of course sections.

- Many departments have specific guidelines, requirements or recommendations for faculty to consider.

- Departments will also be balancing the contingencies mentioned above to develop a plan to ensure the courses with a direct impact on student degree progress and success will be able to take place in-person.

2. Consider how you may pivot your chosen learning mode to respond to unexpected external or personal events.

- Unexpected personal or external events, such as fires, outages or illness, may present themselves at any time throughout the semester, so we encourage you to consider how you may respond in the unlikely event that conditions change for you or your students.

- Create a backup plan for at least one module of your course before the semester starts. This will allow you to be ready, flexible, and resilient.

3. Consider student workload in light of the learning mode.

Student workload is equivalent across learning modes. The difference between learning modes is what is often defined as “in-class” instructional time.

Student workload expectations for a standard1 credit hour is 3 hours per week. For example, a 3-credit course includes approximately 135 hours of student workload during the semester with an optional final exam (9 hours per week * 15 weeks of instruction per semester = 135 hours per semester). For courses taught using face-to-face and/or synchronous online learning, part of the 9-hours of weekly student workload is reserved for class sessions where students and instructors meet synchronously (at the same time), either face-to-face or online.

- Note that the hours per unit for courses classified as activities (C7-14), labs and clinicals (C15-17), sports and musical performance (C18-21), or supervisory courses differ from the standard assumption for student workload (https://academicprograms.humboldt.edu/sites/default/files/howtocalculatescu.pdf).

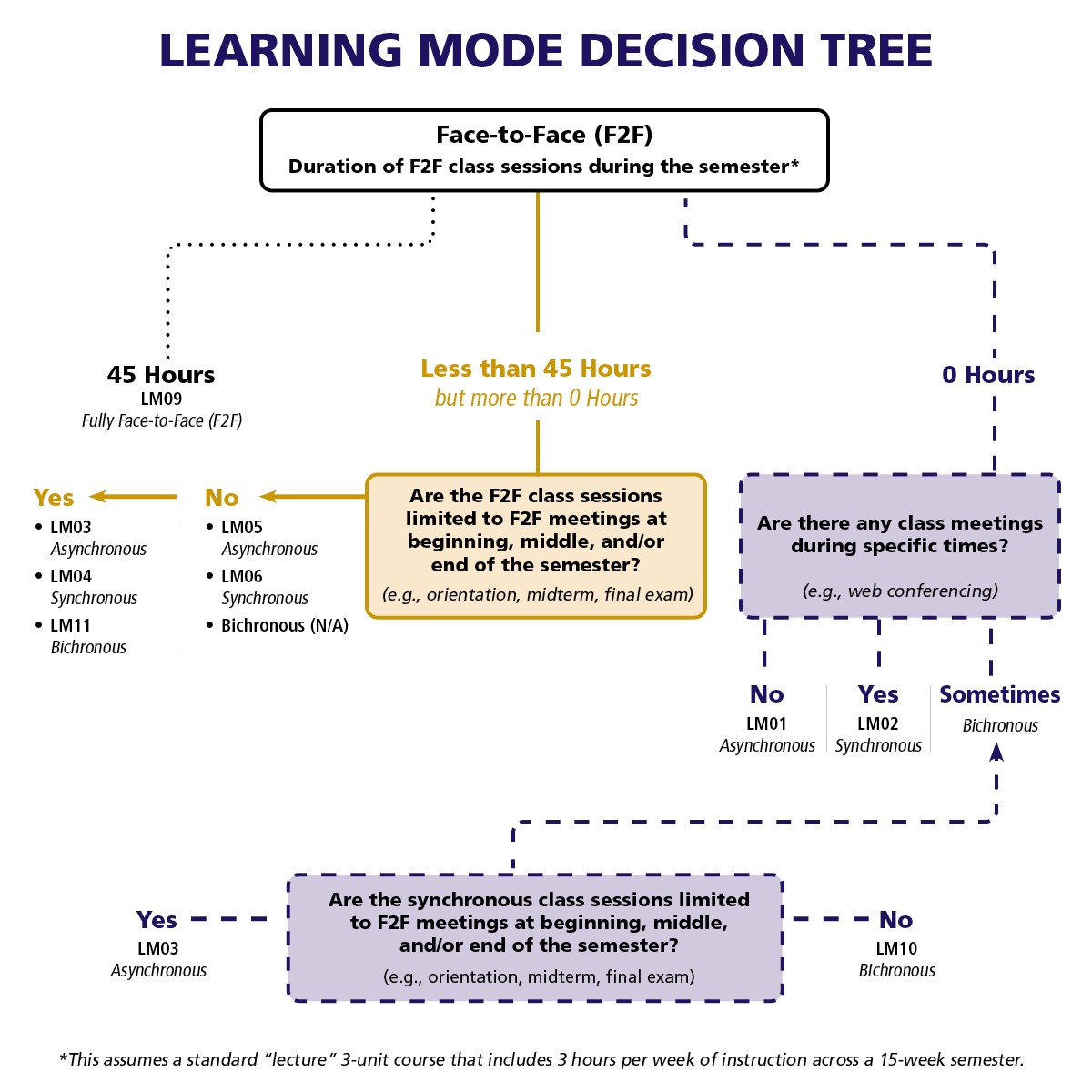

Learning Mode Decision Tree

This decision tree can help you identify the right learning mode for your course.

| LEARNING MODE | CODES |

|---|---|

| Fully Online |

|

|

Occasional Hybrid Occasional F2F Class Sessions |

|

| Frequent Hybrid Partially online and partially in-person |

|

| Fully Face-to-Face (F2F) |

|

| HyFlex |

|

CSU Definition:

- Web delivered instruction available to students 24/7. Learning occurs through online channels without real-time interaction.

In other words...

- A course that is fully online and does not meet at any specific day/time. Instructors post course materials and activities for students to complete using the Learning Management System (iLearn). While the course normally has weekly deadlines, students can complete their work at the times most convenient for their schedules in order to meet the deadlines.

Example:

- The instructor posts lecture videos and readings each week followed by discussion forums and periodic assessments on that content.

Pros

- Provides flexibility in terms of both where and when to learn for both instructor and students.

- Students can most often consume (read, watch, listen) information and immediately apply that knowledge.

- The only mode eligible for CSU’s CourseMatch program (which makes the course available to all CSU students).

Cons

- There is a lack of immediacy. Students and faculty do not get the instantaneous verbal and nonverbal feedback that is inherent in synchronous experiences. This may hinder communication and engagement.

- Community and interaction have to be more intentionally scaffolded in this mode since the class members are not online together at the same time.

CSU Definition:

- Web or airwaves delivered instruction at specific pre-scheduled days/times recurring each week. Learning occurs through online channels in real-time interaction.

In other words...

- A fully online course that uses a web-conferencing platform (e.g. Zoom) to meet synchronously during a specific timeblock each week. Coursework outside of the scheduled timeblock is often managed within a learning management system, but it is not considered bichronous because no class sessions are replaced with asynchronous activities.

Example:

- Students and instructor in a 3 credit course meet via Zoom on Tuesday and Thursday at 10am each week for 3 hours weekly of lecture and discussion for the fifteen-week semester and potentially during the final exam period. The instructor makes use of iLearn to facilitate approximately 6 hours out-of-class learning in addition to 3 hours of synchronous class sessions each week.

Pros:

- Provides flexibility in terms of location.

- Allows for real time connection between students and instructors, which may improve communication and increase engagement.

Cons:

- This mode requires a high bandwidth stable internet connection and webcam.

- Students need to have consistent access to technology and a quiet space to attend class sessions at the same time every week. This can be challenging for students who are sharing their technology and living spaces with others, or who have caregiving or work obligations that may make it impossible to participate in real time.

- Many faculty found it challenging to remain resilient using this mode during the pandemic, given the additional workload of creating equivalent alternatives to the live sessions for those students unable to participate for various reasons.

CSU Definition:

- Asynchronous 24/7 web delivered instruction with very limited specific date face-to-face or synchronous meetings for orientation and/or mid-term and/or final exam and/or rare single date class meetings for other purposes.

In other words...

- A course that is mostly asynchronous online, but has a few in-person or synchronous online meetings throughout the course of the semester.

Examples:

- An asynchronous online course that meets in-person for a beginning of semester course orientation, a midterm and a final exam.

- An asynchronous online course that meets synchronously on three dates for guest speakers with Q & A.

Pros:

- Provides the flexibility of an asynchronous course, but enabling the instructor to have very limited in-person class sessions for relationship building, real-time discussion, or in-person examinations.

- Because this mode is mostly online already, pivoting to fully online only means changing plans for a few dates should it become necessary.

Cons:

- Requires students to come to campus which could potentially be challenging for students who have relocated during the pandemic (if limited real time sessions are in-person).

- Even though it is mostly asynchronous, this mode is ineligible for CSU’s CourseMatch program (which makes the course available to all CSU students).

- Requires clear course design and organization so students know what is happening when and in which mode.

How do I pivot this mode to fully online if necessary?

- Create a back-up plan to transition any face to face sessions to iLearn or Zoom before the semester starts, just in case.

CSU Definition:

Synchronous web or airwaves delivered instruction at pre-scheduled days/times recurring each week with INTERMITTENT (days/times vary and less frequent than biweekly) face to face meetings for one or more of following: orientation, mid-term and/or final exams, an overview of next phase of course content.

In other words...

A course that is mostly synchronous online but has a few in-person meetings on campus throughout the course of the semester.

Examples:

- A synchronous online course that meets on-campus for a beginning of semester course orientation, a midterm and a final exam.

- A synchronous online course that meets in-person, on campus at a few pre-determined dates/times during the semester to launch each new unit and build community.

Pros:

- Allows students and faculty to mostly learn and teach remotely while giving the opportunity for in-person meetings when it is most crucial for learning.

- Because this mode is mostly online already, pivoting to fully online only means changing plans for a few dates should it become necessary.

Cons:

- Requires students to come to campus which could potentially be challenging for students who have relocated during the pandemic

- This mode requires a high bandwidth stable internet connection.

- Students need to attend synchronous online class sessions in a quiet location where they can talk. This can be challenging for students.

- Requires clear course design and organization so students know what is happening when and in which mode.

CSU definition:

- Hybrid combination of face-to-face and asynchronous 24/7 web delivered instruction. Face-to-face component must meet weekly at specific day/times.

In other words...

- A hybrid course that combines more than 0, but less than 45 hours, of in-person classes on campus with asynchronous online instruction.

Examples:

- A hybrid course that meets in-person on Thursdays for short lectures, group discussions and active learning for part of the “in-class” contact hours. Moreover, short recorded lectures, readings, exercises and reading quizzes facilitate learning outcomes during the other weekly hours. During a typical week, this 3 credit course meets 1.5 hours in-person and student complete an additional 7.5 hours of work.

- A hybrid lab course that meets in the lab on Wednesdays, with all lab preparation work (watching lab technique videos, preparing and submitting pre-lab reports and pre-lab quizzes) taking place asynchronously online.

Pros:

- Allows for the benefits of face-to-face learning experiences (e.g., immediacy of communication, engagement) as well as the flexibility of asynchronous online teaching and learning.

- Faculty can choose the best mode for each learning activity.

- Research studies consistently confirm that the hybrid learning mode is the most effective for student learning and success.

Cons:

- Requires more up-front planning time and intentional course design decisions from faculty in order for course requirements to be clear to students.

- Hybrid courses are prone to ask too much of students, often described as a “course and a half,” so faculty need to be mindful of the combined workload in all modes.

How do I pivot this mode to fully online if necessary?

- The simplest way to pivot a hybrid course is to replace the face-to-face sessions with synchronous zoom sessions, transforming the course into a bichronous course (fully online with both synchronous and asynchronous elements).

- Create a back-up plan for transitioning face-to-face activities into Zoom activities before the semester starts just in case.

CSU Definition:

Hybrid combination of face-to-face and synchronous instruction (see 02 definition above). Both the face to face and synchronous (pre-scheduled broadcast) component must meet weekly at specific day/times.

In other words...

A hybrid course that combines in-person classes on campus with synchronous online instruction.

Example:

A 3 credit hybrid course that meets in-person on campus for 1.5 hours Tuesdays for short lectures and active learning, and meets via Zoom for 1.5 on Thursdays for small group instruction and projects. Student complete approximately an additional 6 hours of work outside of these sessions.

Pros:

- Allows for some in-person learning experiences while reducing the amount faculty and students need to be on campus each week.

Cons:

- Requires more up-front planning time and intentional course design decisions from faculty in order for course requirements to be clear to students.

- Hybrid courses are prone to ask too much of students, often described as a “course and a half,” so faculty need to be mindful of the combined workload in all modes.

How do I pivot this mode to fully online if necessary?

- To pivot this type of hybrid course, the instructor would need to to replace the face-to-face sessions with either additional synchronous zoom sessions or asynchronous elements.

- Consider in advance if replacing F2F activities with additional Zoom sessions or with asynchronous activities makes the most sense and create a back-up plan accordingly.

CSU Definition:

- Combination of synchronous and asynchronous instruction throughout the term.

In other words...

- A fully online course that combines synchronous and asynchronous class sessions throughout the term. This is not considered fully online synchronous (see LM 2) because some class sessions are replaced with asynchronous activities. For a 3 credit course, therefore, there is more than 0 and less than 3 hours per week of synchronous class sessions.

Example:

- Students and instructor in a 3 credit course meet via Zoom 1 hour per week while completing other “in-class” and “out-of-class” time through asynchronous learning activities in iLearn (approximately 8 additional hours of work per week).

Pros:

- Allows for some real time connection, but reduces the overall duration of high immediacy, high bandwidth sessions.

- Faculty can choose the best mode for each learning activity.

- Provides the greatest flexibility for faculty and students.

Cons:

- Requires clear course design and organization so students know what is happening when and in which mode.

CSU Definition:

- Combination of synchronous and asynchronous instruction (see 01 and 02 definitions above) with INTERMITTENT (days/times vary and less frequent than biweekly) face to face meetings for one or more of following: orientation, mid-term and/or final exams, and overview of next phase of course content.

In other words...

- A course that is mostly bichronous online (combines asynchronous and synchronous online modes) but has a few in-person meetings on campus throughout the course of the semester.

Examples:

- A bichronous online course that meets in-person for a beginning of semester course orientation, a midterm and a final exam.

- A bichronous online course that meets in-person at four specified dates/times during the semester to launch each new unit and build community.

Pros:

- Allows students and faculty to mostly learn and teach remotely while giving the opportunity for in-person meetings when it is most crucial for learning.

- Allows faculty the greatest flexibility for using the learning mode that best meets specific learning outcomes.

- Because this mode is mostly online already, pivoting to fully online only means changing plans for a few dates should it become necessary.

Cons:

- Requires students to come to campus which could potentially be challenging for students who have relocated during the pandemic.

- Requires clear course design and organization so students know what is happening when and in which mode.

How do I pivot this mode to fully online if necessary?

Create a back-up plan for transitioning any face to face sessions to iLearn or Zoom before the semester starts just in case.

CSU Definition

There is no official CSU definition or Learning Mode for the HyFlex mode, so there is no method to accurately list it in the course schedule. Departments often offer two sections two sections taught by the same instructor, who then combines the two sections into a common iLearn site. One section is offered Fully Online LM 01, and the other is Face-to-Face LM 02, with an enrollment cap of the Face-to-Face course that does not exceed the capacity of the physical space.

In Other Words...

HyFlex is a student-driven learning mode which grants student autonomy to complete the course requirements by engaging in-person or online, synchronously or asynchronously, at their own discretion throughout the term. In the course design, the instructor teaches in-person and also presents equivalent, though not necessarily identical, learning experiences that support student achievement of learning outcomes outside of the in-person experience

Examples

- In-person + online asynchronous. An instructor teaches 3 hours a week in-person on campus and provides equivalent online asynchronous activities for students to engage with the course concepts and demonstrate achievement of learning outcomes, for example through readings, transcripts, and recorded (not live) videos.

- In-person + online synchronous. An instructor teaches 3 hours a week in-person on campus and simultaneously provides equivalent online synchronous learning activities for off-campus students to engage with during the session, for example through web conferencing.

- In-person + online asynchronous + online synchronous. An instructor teaches 3 hours a week in-person on campus, provides equivalent online asynchronous activities for students to engage with the course concepts and demonstrate achievement of learning outcomes, for example through readings, transcripts, and recorded (not live) videos, and also provides equivalent online synchronous learning activities for off-campus students to engage during the session, for example through web conferencing.

Pros

- HyFlex supports students in their self-determination and persistence since they can make their own choices about how, when, and where to participate in planned learning activities, based on their personal learning needs and outside work and family obligations.

- Hyflex pushes the limits of educational innovation in terms of pedagogy and technology, prompting creative ways to reimagine higher education post-pandemic.

- HyFlex enables institutions to expand beyond the physical capacity and geographic constraints of a classroom, to increase access to courses, and support student enrollment and retention goals.

Cons

- HyFlex is a labor-intensive and complex teaching mode for faculty, due to the additional effort and expertise required to prepare, facilitate, and manage class sessions in two or three parallel learning modes. This is most challenging for faculty new to online teaching.

- To ensure meaningful equivalent experiences for students in all modalities offered in a HyFlex course, instructors need to have skills in designing and implementing inclusive and active learning strategies while teaching with technology.

- HyFlex teaching is still new to many faculty, students and institutions. Early research published since 2007 shows the potential for improved student access, satisfaction, and, in some cases, improved learning. Ongoing research efforts include assessing the experience of minoritized students in HyFlex classes and evaluating the potential for closing equity gaps in higher education.

How can I pivot this mode to fully online if necessary?

- The HyFlex mode pivots easily to fully online, since the instructor has already provided equivalent, though not necessarily identical, learning experiences outside of the in-person experience to support student achievement of learning outcomes. In a pivot to fully online, the instructor can suppress the in-person class sessions and move to a fully online bichronous mode, with optional synchronous sessions, so that students can still choose to attend synchronously or asynchronously.

Additional Learning Mode Considerations

The choice of learning mode — whether one chooses face-to-face, online, asynchronous, synchronous or bichronous — raises fundamental questions about how we uphold our campus' mission of social justice in a global era of racial, health and economic pandemics. Throughout the FAQ are critical learning mode discussions related to CSU requirements, campus governance processes, the fiscally responsible stewardship of state funds, and most importantly, our commitment to justice, equity, diversity and inclusion. Responses to these frequently asked questions attempt to balance the intersecting perspectives at the system, campus, and individual levels, with a focus on student success.

CSU Fully Online is a searchable database that supports two purposes related to Learning Mode:

Assembly Bill No. 386 (AB386): CSU Fully Online supports legislative compliance with AB386 by providing a searchable database for CSU students to find and register for fully online (LM01) courses that may have available seats at other CSU campuses. Section 66763.5 of this bill states that the enrollment of a student at a host campus may be counted in the calculation of headcount or full-time equivalent student enrollment at the host campus, but there is no direct payment to Academic Affairs to offset the instructional cost, like in CourseMatch.

Course Match: CSU Fully Online supports the opportunity for a CSU campus to voluntarily reserve a certain number of seats (minimum of 10) in a fully online asynchronous course (LM01) to offer to external CSU students. If the course is accepted into the program, and if at least one external student enrolls in the course, then the host campus does receive compensation in the form of a direct payment to Academic Affairs, which may offset, but not completely cover, the instructional costs. CourseMatch enrollments may not be counted in the calculation of headcount or full-time equivalent student enrollment at the host campus.

CSU Fully Online & AB386: CSU Fully Online supports compliance with AB386 by providing a searchable database for CSU students to find and register for fully online (LM01) courses that may have available seats at other CSU campuses.

Course Eligibility: Fully Online (LM01) describes courses conducted completely online in an asynchronous environment with no scheduled meeting or exam times. These courses are added to the CSU Fully Online database automatically, without the ability for exemption. Each campus determines a shortened enrollment window for AB386 courses, for SF State Fall 2020 it was August 17-23, during which time available seats for these courses were made visible to external CSU students.

Student Eligibility: Generally, students are able to take one course at another campus at a time, but exceptions can be made on a case by case basis. External students are only able to see these courses and register at a particular time during the enrollment window for AB386 courses, as determined by the host campus.

Student Impact: During the period that available seats are opened concurrently to SF State and CSU students, there is the chance that a late-enrolling SF State student would no longer have access to a seat that would have otherwise been available. In a more positive scenario, it is possible that an external CSU student may be provided the chance to complete a course that helps them move towards degree completion, with little additional impact on the workload of faculty or instructional cost to the institution.

Financial Impact: AB386 enrollments are counted towards FTE, CourseMatch enrollments are not. As such, it may happen that SF State be obligated to deliver a course, and assume the instructional cost, of a course that would not have had enough local enrollments to prove viable otherwise. Some departments may see this as an opportunity to generate interest in their programs across the system which, in consultation with the college administration, might be seen as a worthy investment.

Course Eligibility & Process: Only fully online asynchronous (LM01) courses that have been approved by the CSU Chancellor’s Office are eligible to be listed as CourseMatch courses within CSU Fully Online. The general preference has gone to accepting fully online asynchronous (LM01) courses which also satisfy undergraduate general education requirements, have historically low DFW rates, and have benefitted from some level of campus sanctioned quality assurance process, such as when the instructor has completed the equivalent of the CEETL Online Teaching Lab.

Student Eligibility: At the start of the enrollment period, which for SF State was June 1 for Fall 2020, external students will be able to enroll in reserved CourseMatch seats until they are filled, and SF State students will be able to enroll in the regular class seats until those are filled. If, upon the end of the enrollment period there are still reserved CourseMatch seats remaining, SF State can then open those seats to SF State students.

Student Impact: Some SF State students may find that the course they want has filled and they are placed on a waiting list, even though other seats remain open to external students via CourseMatch. In these cases, the department may raise the enrollment cap of the course or reduce the number of reserved CourseMatch seats, as long as a minimum of 10 seats are still allocated for external students. Regardless, any open CourseMatch seats will be returned to the hosting campus prior to the start of the semester so that home students can enroll or be added from the waitlist.

Financial Impact: If a campus offers an approved CourseMatch course and at least one external student enrolls, the campus will receive a modest payment, generally up to $3,400 for the first 10 students, which can offset, but not completely cover, the instructional cost.

- As evidenced in the LM Decision Tree, LM03 is an ambiguous code since it may indicate that the course does, or does not have F2F class sessions. This is problematic from a student perspective, which is why LM10, rather than LM03, is recommended for bichronous courses in Spring 2021.

- There is no CSU established learning mode that communicates “optional” synchronous sessions in a fully online course, so LM10, with a note in the schedule and syllabus, is the only way to communicate this option at this time.

- Learning Modes 02, 03, 04, 06, 10 & 11 include synchronous online learning sessions. To ensure equity and access, faculty are encouraged to: 1) use these synchronous sessions for optional opportunities to deepen learning and build community, 2) provide asynchronous alternatives to synchronous learning opportunities and assessments, and 3) communicate this flexibility in the syllabus and in the notes in the course schedule. Synchronous sessions, even optional sessions, can only be scheduled during the regular time block for that course.

- LM11 only indicates that a course has intermittent F2F class sessions and there is no parallel code that indicates that a course has regularly scheduled F2F class sessions. Therefore, it is likely that LM11 will be incorrectly applied to both types of courses; an additional LM code is needed to resolve this issue.

- AB386 mandates that all fully online courses with available seats be made available to other external CSU students during a determined amount of time, and the enrollment of a student at a host campus may be counted in the calculation of headcount or full-time equivalent student enrollment at the host campus. To be further determined at SF State is whether this fully addresses the instructional costs of the host campus for these external students. This may be a critical issue for our campus not only in the COVID short-run, but also in the campus long-run since it is a likely assumption that the portion of courses taught online will continue remain higher than pre-COVID and more CSU students will opt to attend their “local” campus after the crisis.

As per Academic Senate Policy S21-264, department faculty, in consultation with college councils, are responsible for determining and reporting the learning mode for each course so that it is accurately communicated to students via the course schedule. Departments are most familiar with their faculty, students and disciplinary content and materials, and are ultimately responsible for ensuring the quality of education and student achievement of learning outcomes within their departments. There is no modality that can be determined universally superior to another, they all have a place in the spectrum of offerings within a university, so it is important for the departments to make informed decisions regarding the modality for each course. Departments need to ensure that faculty assigned to teach courses in any learning mode are appropriately prepared.

Faculty have a great deal of academic freedom within their courses, provided the course components support the achievement of the student learning outcomes and abide by the academic policies and laws expected for all learning modes. As per Academic Senate Policy S21-264, faculty members are expected to use teaching practices that are appropriate to the learning mode advertised in the class schedule, and to seek the professional development and support necessary to ensure a successful educational experience for their students. Although courses must be delivered using the learning mode approved by the department, an instructor teaching an online synchronous course may adapt to unforeseen circumstances by teaching a maximum of 15% of the class sessions during the semester using an asynchronous learning mode.

University-level courses in any modality offer students a certain level of independence in setting their own study schedule, and with that independence also comes an increased responsibility to establish healthy study skills and habits and ask for assistance when needed. Students are expected to identify and use the appropriate time management and study skills appropriate for the modality of the course, and to seek out and access campus resources. Students should keep in mind that a three-unit course, regardless of its learning mode, generally requires a 9-hour weekly time commitment.

As per Online Education Policy (S21-264)

- A department’s faculty, in consultation with college councils, are responsible for deciding which courses (or sections) as well as which degree or certificate programs will be offered in a face-to-face, hybrid or fully online format.

- Although courses must be delivered using the learning mode approved by the department, an instructor teaching a face-to-face course may adapt to unforeseen circumstances by teaching a maximum of 15% of the class sessions during the semester using an online learning mode.

- Similarly, an instructor teaching a synchronous online course may choose to teach a maximum of 15% of the class sessions during the semester as asynchronous online sessions.

- Department chairs and students must be notified of the change in learning mode in either event.

- Conversion of greater than 15% of class sessions requires department approval and should only be done in extreme cases.

Yes, faculty can change the learning mode for up to 15% of a course without departmental approval or, in extreme cases, up to 100% with department approval. In both cases, the change can only move towards the more flexible option for the students (i.e. towards online asynchronous), and the students and the chair must be notified of this change.

The department faculty are the ones to determine which learning mode is appropriate for each course and should be fully informed about the benefits and challenges of each learning mode to make this decision. Nonetheless, given the extenuating circumstances of AY2020-21, departments are encouraged to consider the “bichronous” Learning Mode 10, since it supports the “best of both worlds” of synchronous and asynchronous learning.

To ensure equity and access for all students who do not have the resources or ability to attend in real-time, faculty are encouraged to: 1) use synchronous sessions for optional opportunities to deepen learning and build community, 2) provide asynchronous alternatives to synchronous learning opportunities and assessments, and 3) communicate this flexibility in the syllabus and in the notes section in the course schedule. There is no CSU established learning mode that communicates “optional” synchronous sessions, so LM10, with a note in the schedule and syllabus, is the best way to communicate this option. Synchronous sessions can only be scheduled during the regular time block advertised for that course.

The next questions provide a more thorough discussion on the advantages and disadvantages of fully asynchronous, fully synchronous, and “bichronous,” which combines asynchronous and synchronous learning in the same online course.

Fully online asynchronous learning offers students more flexibility in terms of managing time and access to resources such as a computer, reliable bandwidth, and a physical space conducive for learning. The asynchronous mode also provides more time to process content and think through responses, which is especially useful for people with disabilities and students who are speakers of other languages.

LM01 is the recommended learning mode for fully online asynchronous instruction.

The primary advantage of synchronous online learning is the immediacy of student-instructor and student-student interactions, which can reduce the social and cognitive distance between the individuals in the course and contribute towards a stronger sense of community and belonging. Real-time interaction in a class setting is familiar and comfortable for many students and faculty, given their experience with traditional learning modes in face-to-face courses.

LM02 is the recommended learning mode for fully online synchronous instruction since it allows for synchronous sessions.

Recent studies have shown that a mixture of both synchronous and asynchronous, now commonly referred to as “bichronous,” activities in a fully online course may lead to improved student learning outcomes for some students. According to Drew, Polly and Riszhaupt (2020), research shows that when synchronous communication features are integrated with asynchronous aspects, the online course is more engaging, increasing learning outcomes, positive attitudes, and retention.

LM10 is the recommended learning mode for bichronous instruction since it allows for synchronous sessions throughout the semester, which can be used to build community and deepen learning.

LM03 is not recommended as a bichronous option because it limits synchronous sessions to the orientation and exams. The Academic Senate has developed a resolution against the use of third party online proctoring services for high stakes exams due to the issues of equity, accessibility, and privacy they present, as identified by the CSU Chancellor’s Office. This sentiment carries over, at least in philosophy, to the case of an instructor choosing to use synchronous sessions for the sole purpose of proctoring an exam in real time, rather than for the purpose of building community and deepening learning.

To ensure equity and access for all students, faculty are encouraged to: 1) use synchronous sessions for optional opportunities to deepen learning and build community, 2) provide asynchronous alternatives to synchronous learning opportunities and assessments, and 3) communicate this flexibility in the syllabus and in the notes section in the course schedule. Synchronous sessions can only be scheduled during the regular time block for that course.

Although the addition of synchronous components to asynchronous online courses has been shown to increase engagement, persistence, and improved learning outcomes for some students, it is also important to consider the needs of students who lack the resources or ability to fully participate in synchronous activities due to a number of extenuating circumstances: they may not have regular access to a computer, reliable internet, or a private place to engage in the synchronous sessions; they may have taken on increased responsibilities to contribute to the household or care for family members; they may not feel comfortable vocalizing their personal or political perspectives in a synchronous session when living with family or others who do not share their views; or they may be dealing with other cognitive, emotional or physical challenges that they do not want to disclose.

To ensure the best chance of success for all students, faculty are encouraged to provide students with flexibility by leveraging the benefits of each learning mode. Asynchronous elements, such as readings, videos and forum discussions, allow students equitable access to the core course components required to achieve the learning outcomes, whereas optional synchronous activities, such as real-time course orientations, discussions, additional office hours and group-study time, can be used to deepen learning and create a sense of community and belonging for those who are able to participate. In all situations, as noted previously, synchronous sessions can only be scheduled during the timeblock posted in the course schedule to not conflict with other courses at that time.

The Center for Equity and Excellence in Teaching and Learning offers multiple forms of support to faculty and departments interested in learning more about teaching in these learning modes. To learn more, please register for faculty development offerings, or request a consultation with an instructional designer.

Additional references related to synchronous and asynchronous learning are also listed below:

- Martin, F., Ahlgrim-Delzell, L., & Budhrani, K. (2017). Two Decades (1995 to 2014) of Systematic Review of Research on Synchronous Online Learning, American Journal of Distance Education, 31(1), 3-19

- Martin, F., Polly, D., & Ritzhaupt, A. (September, 2020). Bichronous Online Learning: Blending Asynchronous and Synchronous Online Learning. Educause Review.

- Peterson, A.T., Beymer, P.N, & Putnam, Synchronous and Asynchronous Discussions: Effects on Cooperation, Belonging, and Affect, Online Learning 22, no. 4 (2018): 7–25.

- Yamagata-Lynch, L.C. Blending Online Asynchronous and Synchronous Learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 15, no. 2 (2014): 189–2